Section 1: The Domestic Sphere

In the United States during the late 1700s, society was sectionalized into male and female spheres of influence. Although the new nation was conceptualized as a republic based on equality under the law, such universal agency was pragmatically understood to be reserved for white males. Men were viewed as “founders,” and as such, they were afforded full participation (and the opportunity for leadership) in every institution, including government, business, home, and church. Women’s influence, on the other hand, was marginal, limited to the men with whom they had direct association.

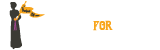

Future First Lady Abigail Adams (1744-1818) expressed this sentiment to her husband, John, as he and other members of the Continental Congress were laying the groundwork for the United States. She was rightly concerned that women’s rights would be left out of the new nation’s laws.

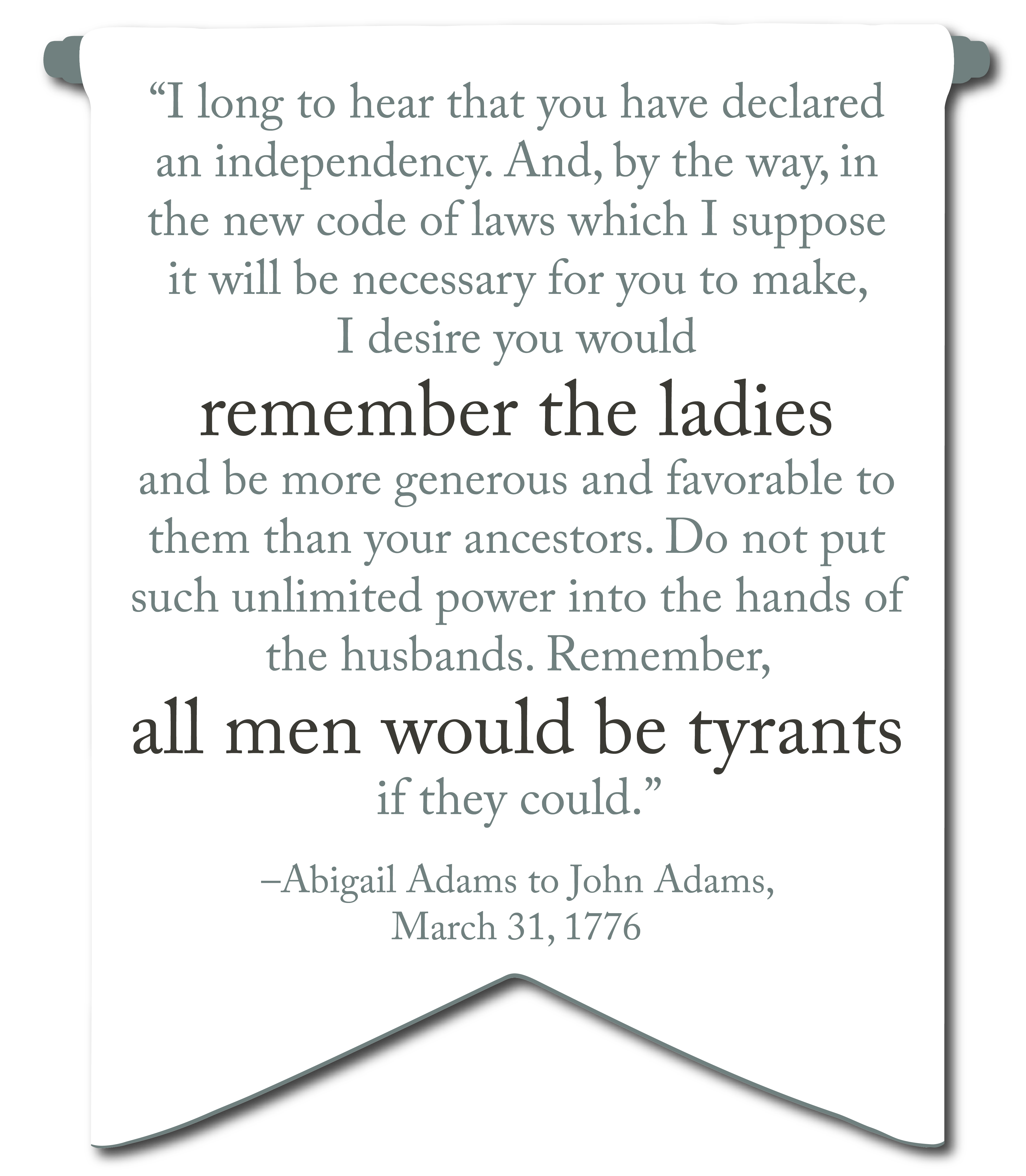

At that time, only a white woman without the “guardianship” of a man could own property, sign contracts, and file lawsuits. As soon as she married, her rights were forfeit. Yet, marriage was almost inevitable for women, as it was a societal expectation and quite often a financial necessity.

In her letter, Adams also warned: “If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.” Despite her threat of immediate retaliation, it took 144 years before the federal government “remember[ed] the ladies” with the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution. The final “march to victory” for this historic piece of legislation took place in Tennessee.

In general, women were confined to a life within the home, and those who tried to expand those boundaries were ostracized, even punished. Interestingly, for the women who were among the earliest European immigrants to East Tennessee, they garnered more equality than their counterparts who remained in coastal cities. When small mountain farms produced only enough to sustain its inhabitants rather than to sell for profit, women retained considerable influence and status, especially within the nuclear family. When men became involved in trade or obtained a professional position, however, women’s status inevitably declined.

[A Beloved Woman’s power]…can by the wave of a swan’s wing deliver a wretch condemned by the council and already tied to the stake.

Race to Chota by Bernie Andrews; from Pat Alderman, The Overmountain Men, 1986, courtesy of the Overmountain Press

Unlike white women, Cherokee women were the equals of Cherokee men, not just in the home but across the whole of Cherokee culture, including politics, economics, and religion. Cherokee women owned property and could initiate a divorce.

Cherokee kinship is based on a matrilineal structure (relating descent through the female line), and the concept befuddled European immigrants accustomed to a patrilineal (male) world view. In 1757, when the great Cherokee leader and diplomat Attakullakulla visited William Henry Lyttelton, the colonial governor of South Carolina, he was surprised to see that no women were present at the trade negotiations. Attakullakulla asked the governor, “Since the white man, as well as the red, was born of woman, did not the white man admit women to their council?” Lyttelton was so taken aback by the question that he took several days to respond.